Restricted Frequency #135

Seize the Art Fair, Chris Ware's Acme Novelty Library #20, and an anecdote from a failed revolution.

1.

The Acme Novelty Library #20 (which you wouldn’t know was The Acme Novelty Library #20, not right away, not on first glance) sat on my shelf for about 5 years, and traveled with me between 4 different cities before finally being read.

Not because it’s big or daunting in any way, but because of perhaps the tedious demeanor implied by its unique Chris-Ware-ness; the four panels that detail a character’s fall off a bike, the five panels (some of them very small) that detail the picking of a pimple, the drip-drip of a ceiling leak into a bucket. But these are the very same reason you’d keep the book around. Over the course of consecutive moves, you’d cleanse your life of the weight of numerous books, but not this one despite not having bothered to read it not once. But every once in a while, when you do pick it up, and you do flip through it, the magic of its storytelling mechanisms are obvious enough for you to keep it around. You know, even without reading it, that it is a true work of art, and as such should stay.

2.

Whenever a new wave of change-demanding protests break out, governments (along with the media) are quick to accuse protesters of not being organized, not knowing what they want, lacking leadership, etc, etc. The same thing happened in Tahrir Square 8 years ago. When waves of protesters reoccupied the square following the ouster of then dictator Hosni Mubarak, the same media personalities that once hailed protesters as the nation’s saviors were then vilified and accused of not being able to agree on anything.

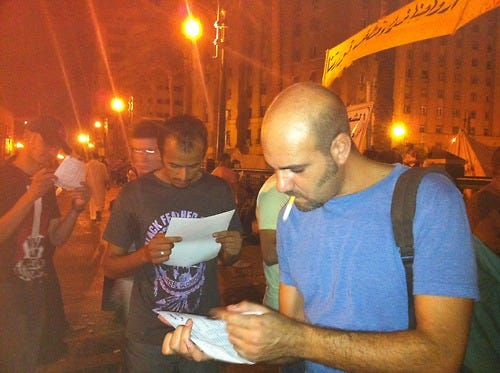

In response, I designed a survey with the help of a number of very bright friends and printed 20,000 copies of the thing (out of my own pocket, btw). On July 8, 2011, We brought them to Tahrir Square and with the help of more volunteers, gave them out and—over the course of a weekend—collected 10,000 filled out forms.

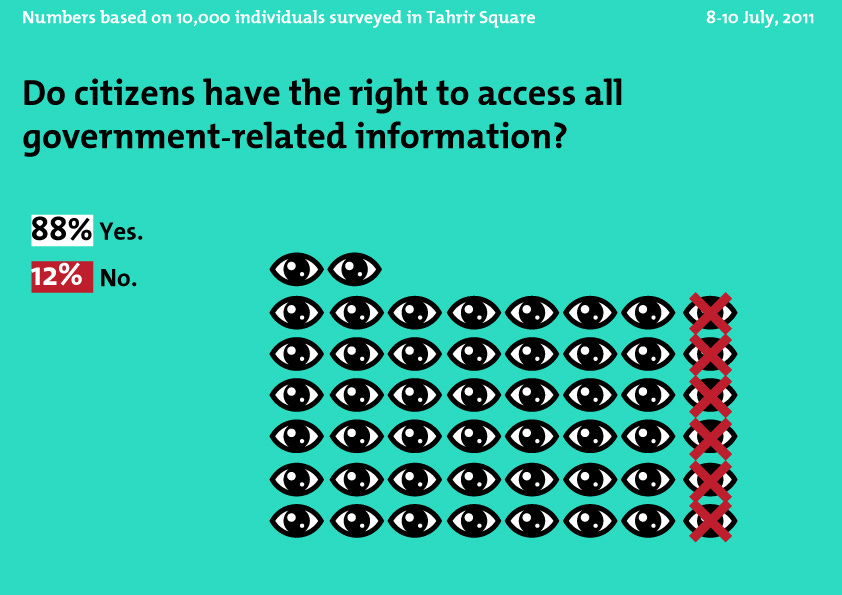

It took well over a year to extract all the data and finally publish the results on what is now defunct web journal I ran called Rolling Bulb. By then, however, the political landscape had already shifted and there was little interest in what protesters wanted or not over a year prior. A lot of the questions in the survey got to the heart of the basic principles of things, and I’d like to think that if you surveyed any group of protesters anywhere at any point in time with the exact same set of questions… results would likely be sooooomewhat similar. But that’s too bold a claim to make, I know.

In any case, in sifting through the carcasses of my digital archives, I came across the infographics I originally created for survey results, and republished them on the new ganzeer dot com.

3.

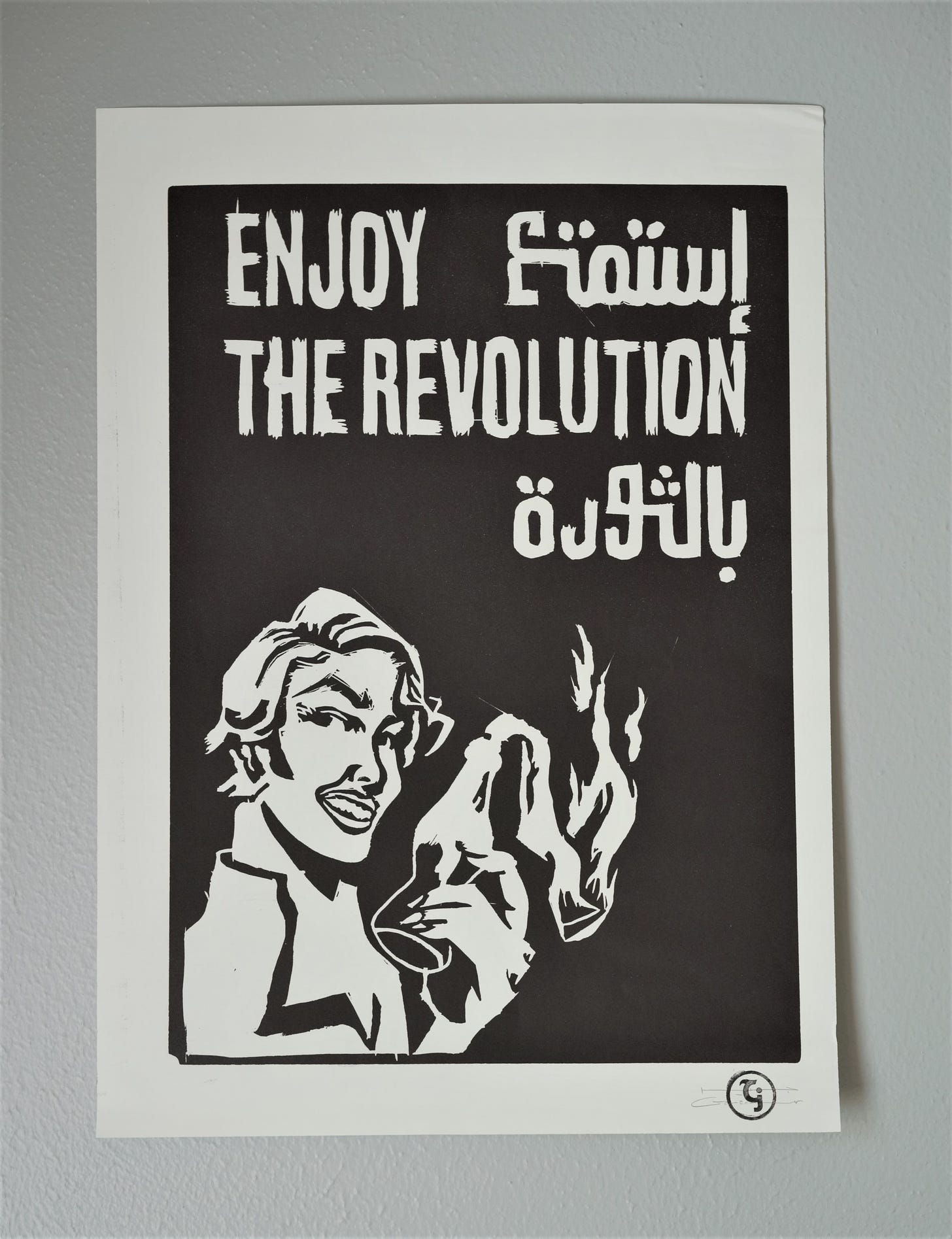

Still clearing my space and mind of older work. On offer this week is this old linoprint from several years back. Only 4 left.

4.

Y’know, I’m not so sure about this whole Art Fair model.

There isn’t a gallerist I’ve spoken to who’s ever had anything nice to say about art fairs. But why would they? It’s a situation where you’re schmoozing and trying/hoping to make a sale for multiple hours on end, for several days in a row, just to cover the exorbitant costs of booth rental. And more often than not, failing absolutely terribly. It’s heartbreaking to see the almost pleading glitter of want, of hope, of despair in a gallerist’s eye as viewers (potential buyers) walk by glancing up at the work on display, pulled in long enough for the few seconds it takes for a gallerist to get their hopes up, only to have them crushed to pieces as said viewer walks on to the next booth. And if you’re there long enough, you see it repeated over and over and over. If you were a terrible sadist, you couldn’t possibly hope for anything worse to unfold before your eyes on relentless repeat.

But you could accuse those gallerists of being masochists, because come the next art fair, they come back for more. The reason they do it of course is that every once in a while, they make that really good sale that seems to make it all worthwhile. Or, even if they don’t, they’re compelled by the need to “stay on the map.” They’re forced to see it as a kind of promotional expense rather than a complete loss of investment.

The people however who almost never incur any losses from these art fairs are of course the fair organizers themselves. It’s a rather perverse situation where the company that sets up the fair not only makes money from booth rental to galleries, but additionally from ticket sales as well. It’s perverse because the people buying those tickets are doing so specifically for the galleries showing at these art fairs and even more so for the very artists they are showing. Take away the art, the artists, and the galleries, and y’know what? Visitors have absolutely nothing to go see.

It seems wholly unfair to me that the people who are the real reason these art fairs are able to happen are the ones incurring most of the losses most of the time. And it seems wholly logical that the best thing they could possibly do is completely do away with the middleman. That they seize the art fair.

To do so however would require the unthinkable: For gallerists to—instead of see one another as competitors—consider each other as partners. To band together to rent out the necessary space to create their own art fair. The cost-per-square-foot will without a doubt be a whole lot less than what they usually pay. On top of that, any revenue made from ticket sales, they can distribute among each other.

It’s an obvious no-brainer, but it requires the audacity to abandon the vampiristic traits of competitive capitalism, and instead think and act like co-op. An industry wide co-op.

(This, I imagine, could very well apply to a fair or convention of any kind, btw.)

Ganzeer

September 7, 2019

Houston, TX